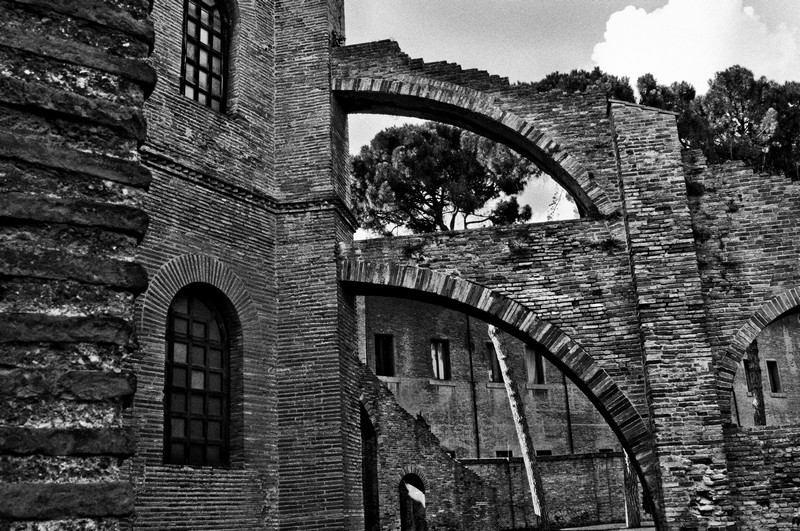

i find the contrast between this stark exterior of the monuments and the lavishly decorated Byzantine mosaics in the interior breathtaking.

below i include Carl Gustav Jung's account of his mysterious experience when visiting the mosaics, in 1933.

Even on the occasion of my first visit to Ravenna in 1913, the tomb of Galla Placidia seemed to me significant and unusually fascinating. The second time, twenty years later, I had the same feeling. Once more I fell into a strange mood in the tomb of Galla Placidia; once more I was deeply stirred. I was there with an acquaintance, and we went directly from the tomb into the Baptistery of the Orthodox.

Here, what struck me first was the mild blue light that filled the room; yet I did not wonder about this at all. I did not try to account for its source, and so the wonder of this light without any visible source did not trouble me. I was somewhat amazed because, in place of the windows I remembered having seen on my first visit, there were now four great mosaic frescoes of incredible beauty which, it seemed, I had entirely forgotten. I was vexed to find my memory so unreliable.

[There follows a detailed description of the frescoes which i skip]

After we left the baptistery, I went promptly to Alinari to buy photographs of the mosaics, but could not find any. Time was pressing this was only a short visit and so I postponed the purchase until later. I thought I might

order the pictures from Zurich.

When I was back home, I asked an acquaintance who was going to Ravenna to obtain the pictures for me. He could not locate them, for he discovered that the mosaics I had described did not exist.

Meanwhile, I had already spoken at a seminar about the original conception of baptism, and on this occasion had also mentioned the mosaics that I had seen in the Baptistery of the Orthodox. The memory of those pictures is still vivid to me. The lady who had been there with me long refused to believe that what she had "seen with her own eyes" had not existed.

As we know, it is very difficult to determine whether, and to what extent, two persons simultaneously see the same thing. In this case, however, I was able to ascertain that at least the main features of what we both saw had been the same.

This

experience in Ravenna is among the most curious events in my life. It

can scarcely be explained. A certain light may possibly be cast on it by

an incident in the story of Empress Galla Placidia (d. 450). During a

stormy crossing from Byzantium to Ravenna in the worst of winter, she

made a vow that if she came through safely, she would build a church and

have the perils of the sea represented in it. She kept this vow by

building the basilica of San Giovanni in Ravenna and having it adorned

with mosaics. In the early Middle Ages, San Giovanni, together with its

mosaics, was destroyed by fire; but in the Ambrosiana in Milan is still

to be found a sketch representing Galla Placidia in a boat.

I

had, from the first visit, been personally affected by the figure of

Galla Placidia, and had often wondered how it must have been for this

highly cultivated, fastidious woman to live at the side of a barbarian

prince. Her tomb seemed to me a final legacy through which I might reach

her personality. Her fate and her whole being were vivid presences to

me; with her intense nature, she was a suitable embodiment for my anima.

The

anima of a man has a strongly historical character. As a

personification of the unconscious she goes back into prehistory, and

embodies the contents of the past. She provides the individual with

those elements that he ought to know about his prehistory. To the

individual, the anima is all life that has been in the past and is still

alive in him. In comparison to her I have always felt myself to be a

barbarian who really has no history like a creature just sprung out of

nothingness, with neither a past nor a future.

In

the course of my confrontation with the anima I had actually had a

brush with those perils which I saw represented in the mosaics. I had

come close to drowning. The same thing happened to me as to Peter, who

cried for help and was rescued by Jesus. What had been the fate of

Pharaoh's army could have been mine. Like Peter and like Naaman, I came

away unscathed, and the integration of the unconscious contents made an

essential contribution to the completion of my personality.

Since my experience in the baptistery in Ravenna, I know with certainty that something interior can seem to be exterior, and that something exterior can appear to be interior. The actual walls of the baptistery, though they must have been seen by my physical eyes, were covered over by a vision of some altogether different sight which was as completely real as the unchanged baptismal font. Which was real at that moment?

My case is by no means the only one of its kind. But when that sort of thing happens to oneself, one cannot help taking it more seriously than something heard or read about. In general, with anecdotes of that kind, one is quick to think of all sorts of explanations which dispose of the mystery. I have come to the conclusion that before we settle upon any theories in regard to the unconscious, we require many, many more experiences of it.

from Jung's Memories, Dreams, Reflections

note: photographs of The Church of San Vitale and the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia